Archive

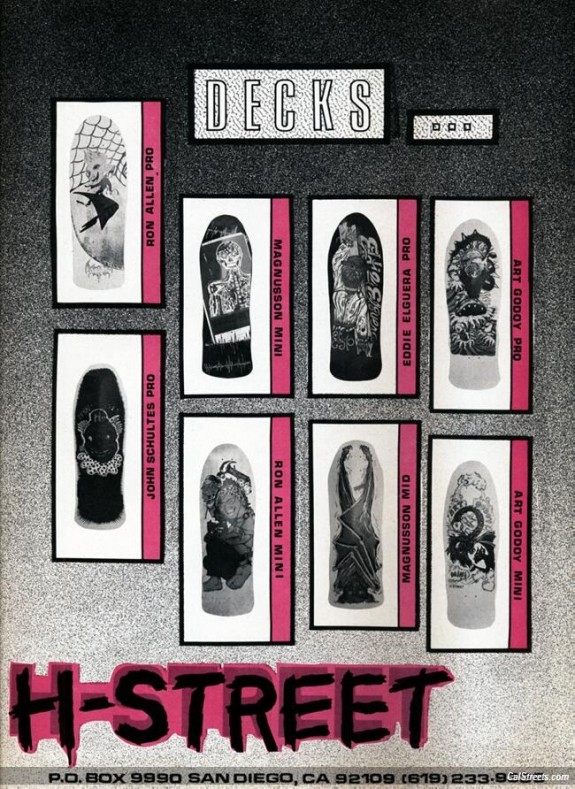

Tony Mag: The H-Street Skateboard Company was formed in 1986 by myself and my bro Mike Ternasky. We hooked up with industry leader George Abuhamad to form the first skateboard company that was run by skateboarders. Inspired by Powell’s success in making skateboard videos but without any large film budget available, we theorized that one might be able to make skateboard videos with cheap VHS cameras and edit them at home on VCRs. This was the first basic home video equipment available early in the ’80s. We also sought out some of the most innovative skateboarders of the time, like Ron Allen, Danny Way and Matt Hensley.

One summer later, the video “Shackle Me Not” was born and would change the way that skateboard videos were made from that point on. A year later, Louisiana swamp rat Sal Barbier was added to the team, along with Alphonzo Rawls and several other top skaters of the day, and the video “Hokus Pokus” was made, which would take the world by storm…together with “Shackle Me Not,” the videos became some of the most watched skate videos. H-Street would eventually produce five major videos, with such notable skaters as Matt Hensley, Danny Way, Ron Allen, Eric Koston, Mike Carroll, Jason Rogers, Colby Carter, John Schultes, Chad Vogt and many other top pros of that era. We also produced a host of innovative and original skateboard products, most notably my Hell Concave, a board with an extreme amount of concave, even throughout the tail and nose.

What were some of your decisions to bring H-Street back?

What were some of your decisions to bring H-Street back?

For one, people in general have asked me to do it for years and I just haven’t had the time, but more importantly, I think that skateboarding is entering a new time, where not only is there an appreciation for old-school brands but also a need for new brands that can step out and offer something that’s different than what has become a pretty basic play: a couple of skaters start a company, get the best riders they can, make only one shape in a few sizes, advertise, make a video, take the team on tour and figure out how to keep them from partying too much. While H-Street was largely responsible for creating this idea that anyone can start a skate company, I think it’s time to step out of what has become a cookie-cutter formula for doing it, too. Having different brands that do different things is a good thing, and I’m looking at remaking H-Street into something that might be a bit different, in many ways.

What do you think were some of the biggest accomplishments of H-Street?

To me, the biggest accomplishment was that we inspired people. I have had so many people tell me over the years that H-Street was an inspiration to them to pursue a dream, whatever it was – start their own skate company, leave a shitty job and become a skate photographer, an artist or whatever. It’s a little-known fact, but I get told that all the time by strangers. It’s also been one of the greatest joys in my own life and has taught me a level of humbleness and appreciation that I don’t think I would have learned otherwise. Of course we didn’t know that would happen at the time, nor was that even an objective. But life has a way of working out in mysterious ways. Positive energy, baby.

Of all the memories you have with the brand, what sticks out in your mind as being the most incredible and unusual?

There are so many memories, it’s almost hard to single something out. Watching guys like Danny Way, Matt Hensley and Eric Koston grow up and see their God-given talent develop them into some of the most amazing skaters ever was like watching art in motion. Watching everyone else grow up with skateboarding and H-Street was also pretty amazing. The number of stories and tales from the H-Street days seems almost limitless, and I’ll be trying to reflect some of that magic on the site, H-Street.com, and perhaps in the DVD set of all the H-Street videos, due out as soon as I have some time to make ’em.

What are some of your expectations?

None whatsoever. H-Street is now just a source of joy for me to work on. I’ve been able to reconnect some amazing people, starting with Ron Allen, and together we’ve come up with some really pretty cool concepts for H-Street. I don’t expect that people will like what we do but instead, I will have an appreciation for those that do.

You’ve brought out a wide variety of sizes and shapes. It seems like you want to appeal to many different types of skaters; any comments on this?

I believe that skateboarding is for everybody. I’m just not into the whole class warfare [of] who is cool enough to ride; let everyone ride and create as large a tent as possible. Using that philosophy, I’d like to create products for a variety of different types of riding.

Any final comments?

Only The Faithful.

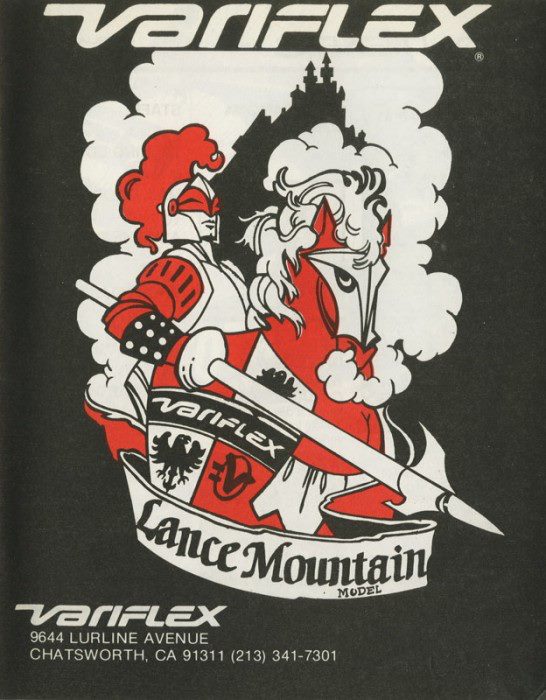

ALL THE YOUNG DUDES, ANNOYING ON PURPOSE, THE WILD ONES Steve Alba and Lance Mountain On the Origins of Inland Skate Heroes, and SkatePunk.

ALL THE YOUNG DUDES, ANNOYING ON PURPOSE, THE WILD ONES Steve Alba and Lance Mountain On the Origins of Inland Skate Heroes, and SkatePunk.

In the parking lot at Malibu during a south swell in August of 2010, Steve Olson said he wasn’t the Missing Link. I had told him I wanted to interview him for the end of Chapter Five of the skateboard book, because he was a major player toward the end of the 1970s, and I was hoping he would be the skater I was looking for – the first major figure who didn’t start out as a surfer. The guy who was the figurehead for what skateboarding would become in the 1980s – as Skateboarder Magazine folded and Thrasher started up, and skateboarding moved away from the sunny surf to the shady turf.

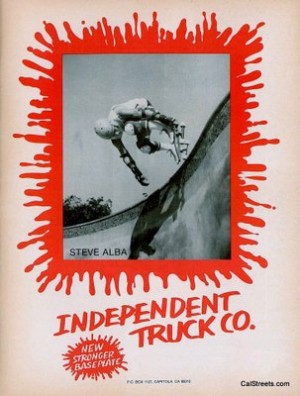

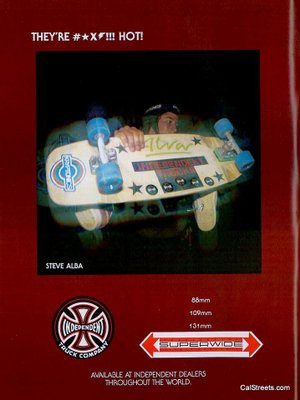

Olson said he wasn’t that guy, but Salba was. I knew we had a good portrait of Salba taken at the Vans skate park and I was going to contact him and then I remembered that curious German chap named Konstantin Butz who had emailed the California Surf Museum in Oceanside saying: “I am a Ph.D. student from Cologne, Germany and the working title of my dissertation is “The Californian Body in Rebellion: An Intersectional Analysis of Skateboarding and Hardcorepunk.” Basically, I deal with the phenomenon of skatepunk and its site-specific “origins” in suburban Southern California and the local punk and surf culture. In that, I focus on the body and body theories.”

Huh? And I thought I was weird.

But Julie Cox at the CSM sent Konstantin to me and I loaned him my pass to get into the Action Sports Retailer show in San Diego and pointed him in some directions I was only learning myself. Mo at Thrasher. Steve Olson.

And he returned the favor by letting me use his interview he recorded with Steve Alba and Lance Mountain at the Fontana Skate Park, on March 24th, 2010.

Mountain and Salba were two guys who came, from out of the east, in the late 1970s, with no surf connection at all. They were skatepark kids, who also were involved in the early days of punk.

These guys were the missing links, taking cutting edge skateboarding away from Led Zeppelin and Foghat and the bushy bushy blonde hairdos of the 1970s and into the jagged, bleached, safety-pinned 80s – with a whole new soundtrack: Blondie, Devo, Cramps, Dead Kennedys.

Steve Alba goes so far as to claim it was skateboarders who invented slam dancing. But these guys were my missing links. These weren’t surfers. These guys were inlanders. Skaters. Skate punks. And they lead skateboarding out of the 1970s and into the 1980s.

Konstantin: So why don’t we just start and talk about how you got into skateboarding and then also into punk rock: which was first?

Konstantin: So why don’t we just start and talk about how you got into skateboarding and then also into punk rock: which was first?

Well, I got into skateboarding first.

Which was when?

It was 1974, right around there.

How did you get into that? Did you grow up around here?

We’re in Fontana right now but I didn’t grow up in this area. I grew up west of here. Back in the day the Hell’s Angels ruled this place. You didn’t come out here unless you were a Hells Angel in those days. Well, Fontana, the city. Not the skate park. Fontana was gnarly dude. They used to advertise for the KKK on the 10 freeway in the 70s and I’m dead serious. I used to trip on that. They had a total KKK chapter out here.

So you grew up west of here?

Yeah, we grew up in Montclair, which was called the San Gabriel Valley and had a 714 area code. Now we’re the Inland Empire: Montclair, Upland, Ontario, Pomona, Claremont. I got into skateboarding because it looked cool and fun to do. My best friend’s brother skateboarded. He was the first guy that I saw… Gary Lazone was his name. Back in those days most guys were skating in a straight line. But Gary Lazone could do nose wheelies and tail wheelies and he could do a three-sixty and jump over a broom stick. Then he set up these slalom cones made out of Coke cans or whatever. This guy could actually skateboard, so we used to follow him around and asked him to use his board all the time and after a while he just got sick of us trying to use his stuff. We eventually got our own skateboards and learned to do all that stuff.

The street they lived on had a slight downhill angle, the sidewalk inclined and turned to the right or the left and there was a brick wall where the planters were. That was our way of learning how to go right or go left. We didn’t even call it frontside or backside. One thing led to another and we kept following this guy around and that lead to this alleyway called “Stoner Alley.” We were in sixth grade and we knew down that alley the Mexicans were at one end and the stoner kids were at the other end. They were always kicking people out and getting in fights so we were tripping out: “What’s going on down that alley?”

So Gary Lazone came through with this little buddies following. They jumped over this fence and we were: “What are they doing?”

So, we walked up to the fence but we didn’t jump over cause we couldn’t see them but we could hear them. We could hear that swoosh of pool skating. It’s a weird sound that is hard to describe but once you actually hear the swoosh of pool skating you don’t ever forget that sound.

We went back home but later that day we went back and jumped over the fence and checked it out and saw the little pool there. So, we start riding it, too: start halfway up and try to carve around deep end. That’s all we did.

Why was the pool empty?

This is the mid 70s and California had a gnarly drought going on. If your pool was empty you could not fill it up, because there was a law against it and if you used water, the water meter at your house would show you went through five, six thousand or whatever gallons it takes to fill the pool up. You’d get fined or even go to jail because that’s how serious the drought was.

We skated for a whole year before we got into pools – this was the spring and summer of ’75. After that our focus shifted away from learning nose wheelies and tail wheelies and three-sixties and jumping over broomsticks and going around Coke cans and going down hills and just all the basic stuff.

At that early point, did music play any role in skateboarding?

At that early point, did music play any role in skateboarding?

Well, back in those days, Gary Lazone was God. Not only did he skateboard, but he surfed, he boogie boarded, he played guitar. He knew how to play Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin and Foghat… Ted Nugent. Everything we were reading about in Cream Magazine, a rock magazine that had all these crazy bands on the cover. We started liking bands that looked really freaky and weird: Alice Cooper and David Bowie, and Iggy Pop was another weird dude.

We had no clue who they were but they were in Cream Magazine, which also covered glam rock and punk rock a little bit later. So we looked into the magazines and tripped on that and really got into Kiss and then the New York Dolls: “Who are those dudes?”

I think we were attracted to some whackness from the get-go. When we started skating the music at the contests was hard rock: Van Halen and Santana. But as skate style and music changed the New York Dolls started coming in and then New York City started coming in: the Ramones and Blondie and the Talking Heads and the Cramps all came out of New York. The music started getting crazier I still credit Steve Olson as the first guy to get into punk rock as a skater. He’s the guy that got people hooked.

How did he do that?

He just played this music. I’m pretty sure he saw Cream Magazine, too, but after a while we went out of our way to look for music. If there’s punk rock in New York, why can’t there be punk rock in California or England? At that time punk rock was the Sex Pistols and the Clash and it was all going on at the same time but we were still really little. In ’78 I was 15 so I was just starting to get into it. We hadn’t cut our hair yet. We started getting thrift shop clothes and you’d see Olson with a pair of crazy ass old man shoes that he spray-painted white and maybe put a pink stripe on them or whatever:

“Dude, what’d you do? Where’d you?”

“I just went to this shop, man…”

That was his thing but to this day I go to thrift shops, because you get the raddest clothes. So probably around ‘78, it started changing, and it was definitely Olson who was the first guy getting into it. Then it was me and after me it was probably Tony Alva. And after Alva it’s probably Duane Peters.

I wouldn’t say I’m a punk rocker now because I’m an old fart and don’t really dress the part but Duane’s definitely a true punk because he lives that style. , just out of control f#%@#% chaos – tornado all the time.

I just want a more stable life. I never wanted to stick needles into my arm either. I never got into that because I never saw the point. Why waste your time? But it’s trippy how punk rock and skating collided and bounced off each other for a while.

How did that happen? Why did that happen? How do they fit together?

As I see it, they’re both aggressive and full of do-it-yourself: You can’t buy it, make it. Cause we all did that in the old days: We made your own clothes. We got thrift store clothes and spray-painted them or put paint on them or put zippers on them. We copied England for a while. You like something and you copy it and don’t even really mean to; it’s a subconscious thing. It’s something in the styles you’re digging and that’s just human nature and that’s the seam of life. That’s how it works, man.

Lance Mountain was sitting next to us listening to the conversation. At this point he joins in. In the following Alba’s parts are marked as SA, Mountain’s parts are marked as LM.

LM: Skateboarding had reached this professional level in ’77, ’78, ’79, with guys like this guy here [Salba]. The guys before these guys really dug Led Zeppelin and that music but the next generation found their own music that fit what they wanted it to represent. I think a lot of skaters knew that they were into something that was really special but the world didn’t see it or care about it. And I think it just went hand in hand with punk: “Ok, I’m gonna make people see this. I’m gonna annoy them. I’m gonna show them and be seen.”

SA: I used to be annoying on purpose just to piss people off.

LM: They wanted to get under people’s skins, ‘cause they were really good at something only a hundred people in the world were doing. It was special and interesting but no one cared. They didn’t have big sports saying, “Hey, this is important,” so they went out and said… I know this cause where I went to school there were only one or two skaters and punks at school, and their whole play was different. They just let people know they were there. They didn’t want people to like them really. They just wanted to let them know that they’re there. That music and the skateboarding happened at the same time.

So, what environment was that to make them feel that?

SA: It was just anti whatever they had.

How did you grow up?

SA: Where I grew up we all played Little League and Pop Warner cause that was something to do in those days. Most of us did that. Montclair was a small town and we had only one high school, two junior highs and four elementary schools. So the people who I grew up with, from eight years old all the way until high school, they were all my friends and buddies, and when first I started skateboarding, they were, “Oh, whatever, this guy is…”

They didn’t give me too much trouble for it because it was that fad thing. You’re cool because you’re skateboarding. But when I started getting into punk rock, they just wanted to disassociate because it was different and it was weird and didn’t go with the flow and status quo.

At first I couldn’t understand why friends who I hung out with and who I played sports with wouldn’t trust me anymore and made fun of me. I tripped on it. It didn’t really hurt my feelings or whatever. I just figured it was me against you, us against them. They were jocks, we were punks. If they had long hair, we’d cut our hair short. If they wore flare pants we wore tight pants. If they wore whacky shoes we wore Converse or the weirdest, loudest shoes we could find. Everything we did was anti everything they did. We were different.

LM: Most of the early skateboarders were the goofy guys. They were more creative and interesting and then a few years later it became more a rebellious and violent thing. But at first skateboarding was for creative and artsy dudes. Olson wasn’t an aggressive angry, anti, violent dude. He was a creative, interesting dude.

The early punk bands were creative and interesting and then two or three years later they were the more aggressive football skinhead punks. In the beginning the skateboarders were more creative and quirky and that music… I remember, when I was young it was all Led Zeppelin but I used to hear a radio show called “Dr. Demento” and it was all this comedy music, – silly, funny music.

Dr. Demento played Devo and I thought: “This is an interesting band.” At the skate contests they’d play rock, rock, rock. Then I went to this contest and all of a sudden they were playing Blondie. Steve had a Devo shirt and I was: “That’s that band!” And pretty soon the skaters seemed to say: “Oh, that’s our music.”

SA: He’s right about… we were the younger guys. Skateboarding already had its established stars at that point. The Dogtown guys were the first guys, but once they kicked the door down a whole bunch of new guys came in. It was me, Steve Olson…

LM: It was a skate park thing.

SA: Yeah, it was all the skate parks.

LM: The early skateboarders were trying to make it an accepted sport, then these guys came along. The Dogtown guys did a lot of vert skating but supposedly you can’t judge it. I mean they never really had a vert contest for those dudes ever. And when they did, Steve won the first one. So okay, this is a new wave. This is a new way of doing things. That’s the same time I believe punk was getting…

SA: Definitely! It all happened simultaneously. The skaters before us had long hair and were surfer guys. They were cool – some of them were actually really cool. But at the same time they were really afraid of us because we were taking away what they had. That’s when pool riding came in; pool riding turned into park riding. And then later park riding turned into ramp riding. And then later ramp riding turned into mini-ramp riding and then street started to happen.

Did you use the term “skatepunk”?

Did you use the term “skatepunk”?

LM: No, that’s more …

SA: We didn’t use it. Originally, I think, it was just made up by Mo and the guys at Thrasher. Really more of a joke.

LM: That’s that second stage of punk. The original guys were into the dorky, arty music. That was a lot different than this second wave of aggressive skate rock.

SA: I’d say it began in 1978, so in ’79 and ’80 the first wave of guys was me, Alva, Duane. Then the second wave of guys when hardcore came in, it was different. Not to say that it wasn’t any better or any radder, cause it was alright. But I think the original punk rock was better. So, there was a first wave and there was a second wave.

So, could you compare that to what was going on in the L.A. punk scene? Because there you had X and the Germs and then you had Black Flag.

SA: Well I grew up with all those bands. The funny thing is, dude, we were kids coming in to watch all those bands. We were 15 when we first started going to the Masque [a pioneering punk club in Hollywood, which ran shows intermittently from 1977 to 1979]. I went to the original Masque, and there’s not a lot of people who can claim that. At first it was a very small group of people, and it was almost: “We’re hipper than all the other people.” I’ve seen every band L.A. had to offer probably at least eight to ten times. That was what we did, man. We just followed all the bands.

Were there bands who had a real connection to skateboarding?

I wouldn’t say that we were connected to skateboarding with those guys at all. They were aware of what we were doing because at the same time the skateboarders were the same guys that made up slam dancing. That was our version of Pogo – which was English. Slam dancing was our version of the pogo in California and it was me, Tony Alva, Steve Olson, Fausto Vitello.

When was that?

SA: This was in San Francisco in ’78 when we saw the Clash, Dead Kennedys and the Cramps.

LM: Instead of Pogoing vertically…

SA: …we just crashed into each other, man.

How did you come up with that?

SA: We wanted to get up on stage. ‘cause the Clash was gonna play and we wanted to touch the same stage that the Clash was on. The Clash was God, as far as punk rock bands go. The Sex Pistols faded, and let’s face it, the Pistols were rad on record but they sucked when Glen Matlock wasn’t with them.

I started playing guitar when I was 18, right around the same period. I was learning how to play and getting better and better as time went on. I paid attention to music and paid attention to guitar players and that’s why I was always trying to get up in front of the stage and would do it at any cost. In those days they didn’t have barricades. You got crushed. When we saw the Clash at that show, I’m telling you man, all of us, all we wanted to do was touch the damn stage that the Clash was on.

And that’s how you came up with the slam dance?

SA: Yeah, we were trying to get to the stage no matter what it took. We were drunk off our ass. We were drinking heavy. I’m not gonna say we weren’t cause we were. And all the other guys were probably loaded up on drugs. But yeah, it was rad. We’d climb over the crowd, dance to ourselves. I remember between the Dead Kennedys playing and waiting for the Clash to come on, we were so amped. It was energy. We just wanted to have more music.

And when the Ramones came out of the PA system between the Dead Kennedys and the Clash, we loved the Ramones at that time and we just started getting crazy and pulling each other down and hitting each other and tackling each other and sliding into each other and one thing led to another. We crashed into the crowd and the crowd started to get mad pushing back and we’re “F@#%@#% you!” and cracking the crowd.

I got in a fight with two big chicks and everyone was fighting with everyone and it was just nuts. Any time the skaters got together at any show, that’s all our deal was: get on stage. No matter what it took. And that’s how we started the whole deal.

Do you think it mattered that you were there as skateboarders?

SA: Yeah, we thought we were crazier than anybody else. And if we weren’t we’d do anything in our power to be more crazy. That was just our nature.

You said you were very young, 15, when you started going to shows. What did your parents say about that?

SA: Well, half the time my parents didn’t know when we were going to L.A. Half the time I was just telling them we were going to the skate park. I had my own car when I was 16. I was first. And I had a friend – she was a girl – who would drive us around before I had my license.

LM: That’s how skatepunk started actually. When the shows started being at the skate parks.

SA: That did happen. Yeah, it did. At “Pomona Pipe and Pool” they had a Devo day and then later on the Joneses and my band the Wild Ones opened up for them. Olson was playing in the Joneses at that time, so it was rad. Olson said, “Yeah, we’re gonna play. I’m gonna get you guys on the bill.” And it was rad. Even though we couldn’t play it was still fun.

What was your band called?

SA: Back in those days we were the Wild Ones. It was our very first band. We were all into Marlon Brando. We tried to play rockabilly, punk rock or whatever.

Thrasher Magazine came out in 1981. What do you think about the role of Thrasher in terms of music and stuff that? Because people tell me, “That’s where we learned about music; that’s where we learned about punk rock.” And you tell me all about the stuff that was going on before that…

The thing is, Mofo participated in a lot of stuff with us. He was there at the Clash with us and he was the guy who wrote for Thrasher. So he’d already been doing his version of punk rock since ’76 or ‘77. When I met Mo the first time, it was really early ’78. Probably at [the Hester Pro Bowl event at] Newark because he hung out with Kevin Thatcher and Rick Blackheart – and those guys came to skate with us at Upland all the time. So, that’s how we made that connection – San Jose and the San Francisco connection. Most of the guys who were from San Jose started Thrasher Magazine – Kevin Thatcher was the first publisher and editor and Mofo was the first big writer. That was their deal, too and it was do-it-yourself. Fausto founded the magazine and they just started doing what they had to do.

It appears that Thrasher is one of the first magazines that really seems to emphasize this connection to punk…

SA: I’m telling you man, Thrasher in those days, they actively participated in punk rock. Kevin Thatcher included – he would go to shows with us all the time, they all did.

LM: The Thrasher guys were skaters.

SA: Yeah, skated with us. They were the skaters. That’s what they did and they presented what they did and that’s why Thrasher in those days was a little bit different than it is now. All the dudes who wrote for the magazine, they all skated and went to shows. Mo has seen as many bands as I have seen in the city. Once we started riding for Indy I used to go up there a lot. We’d go to Fausto’s house and I would stay there for a week or stay in San Jose with Mofo, since there were all kinds of bands up there, too, that you wouldn’t see in L.A.

But I’ve seen pretty much every single band for the most part. Except for the Sex Pistols, ehm, what other band haven’t I really seen? I’ve pretty much seen them all really. Except for Generation X. That’s the one band I haven’t really seen. But everybody else… Saw Stiff Little Fingers, UK Subs, X. I thought Billy Zoom was rad as hell. The Germs…

LM: Do you remember the first band you saw? Punk band?

SA: The first punk band we ever really saw was 999 and the Dickies after some San Diego thing. That was the first show I remember going to. We weren’t really punk rock yet. We were on the verge.

SA: The first punk band we ever really saw was 999 and the Dickies after some San Diego thing. That was the first show I remember going to. We weren’t really punk rock yet. We were on the verge.

LM: Back then, you didn’t have to look punk rock to be punk rock.

SA: Yeah, I guess you’re right. But in my mind you had to really be punk.

LM: You went to shows earlier than me for sure but the first show I went to, there was a pretty broad spectrum of people.

What show was that?

LM: It was a band called Suburban Lawns. I don’t know how I ended up going there. None of the bands that we really knew or saw were around. It was a lot different when there was no internet. So you’d see an album cover – Blondie or Devo or whatever – and think: maybe this is a good one. But we never saw that they played anywhere. There was this place close to my house and we started going to shows of bands just because like Steve said all we wanted to do was jump around and fly on stage.

We were skating and we just wanted to get more aggressive. We were just stupid, basically. I went to a show and there was a guy doing back flips off the speakers. There was a circle pit and we’d jump from stage and there was a double stack of speakers above that and there’s this black dude doing back flips off of it. We’re just, “Dude!” We ended up talking to him and he was, “Oh, I skateboard everyday.” So, he came to our ramp the next day and he would ride up the wall, take a step from the wall and back flip off. That would be his trick. That’s all he did. He was the “back flip dude.” We’re, “This guy is gnarly!”

Then I remember going to a contest where they were playing Blondie, and I remember Steve’s Devo shirt.

SA: That was Lakewood then.

LM: Yeah, Lakewood. My dad is English and I went to England a few times thinking, ‘Ok, I’ve got to see this music. It’s punk. Were in England. Punk!’ Everything is going on. But punk was completely dead at that time in England. They were all into Motörhead and they were all gnarly…

That was when?

LM: That was ’79. I was thinking, ‘Ok, I’m gonna see all this stuff.’ I went to King’s Road and there was no punk music at all.

SA: When I went there in ’81 I thought I’d see the same thing but by then rockabilly was really big. The Stray Cats were coming in.

LM: So, I didn’t see bands until late. All the bands that we wanted to see weren’t really playing. It was very rare. The Clash came later. I saw them. Stiff Little Fingers… very rare. So were going to all this nonsense L.A. stuff.

SA: It was every weekend, there was something going on. Whether it was Alley Cats, The Plugz or…

LM: Out of all those bands I thought the Adolescents were actually interesting.

SA: Yeah, but they were a little later. We’d go to shows in L.A. and we used to see Mike Ness [from Social Distortion] we used to see Rikk Agnew. We didn’t really know who they were at that time. We didn’t know that until a little later after we started skating and they’d go, “Hey we saw you skating,” and blablabla and “I’m in this band called the Adolescents.” Mike Ness’s bass player was this guy Brent [Liles], we were good buddies and we used to skate at Pipeline; we used to skate at Skatopia. That’s how we met; it was through skateboarding. It was a small world and a group of people who really got into the first wave of all these really early early L.A. bands.

So at some point I said, “We’re gonna try do this ourselves.” But by the time you learn an instrument and get as good as you’re supposed to be the scene has changed. X was still around in ’81 but the Alley Cats weren’t. The Weirdos really weren’t. The Dickies still were. You’d still see Siouxsie and the Banshees at that point. Stiff Little Fingers had a big draw in L.A. The Clash had a big draw in L.A. The Vibrators had a pretty big draw, so…

So, what people today actually call or refer to as skatepunk that was something that came later?

LM: I think skatepunk is later when all the skaters started making bands. They did the same as the punk guys: ‘This is easy. I can play this chord. Why don’t we do this, too?’

A lot of skateboarders actually made up bands. That’s what skatepunk is, isn’t it?

SA: For me, when I think of skatepunk the first band that comes to mind would be JFA [Jodie Foster’s Army]. But I know those guys pretty damn good; I’ve known them for years. They don’t even really pitch with skatepunk cause that’s a term that doesn’t really span the horizon of what they are. At the same point they were definitely the forerunners of it. And they were regional, too. There was the Big Boys from Texas, JFA was from Phoenix.

Would you call Agent Orange a skatepunk band? It’s a term that’s a pigeonhole to me.

LM: Agent Orange were in a lot of skateboard videos. So, that’s why people would consider them skatepunk.

What skate videos would be…

LM: They were in a Vision video. I think the whole soundtrack was Agent Orange.

What other videos should I look at? What about Santa Cruz’ Streets on Fire?

SA: I was in those.

I mean, they’re full of SST bands, right?

SA: They licensed them out to Santa Cruz to get more exposure for SST, originally. But it was cool that we could actually use some of these bands. I was stoked on my couple of songs on there. To this day people ask me about those songs. It’s funny.

Which songs are you skating to in that?

SA: Well, there’s a song called Instro. That’s one I wrote. The one that goes, “Dadadada.” that’s my band and then I think we did Kings of Trash on the other one.

Could you choose the music for the videos?

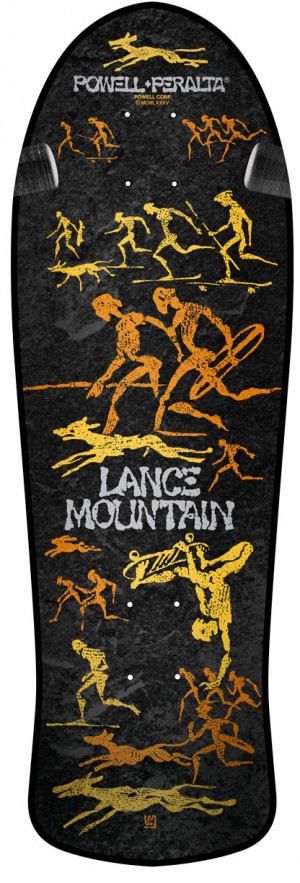

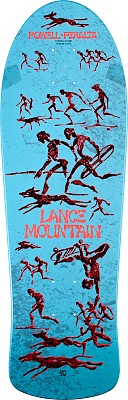

LM: No, when I rode for a company called Powell Peralta, Stacy Peralta made the first skate video. There were movies before but that was actually the first video made. We didn’t pick our music back then. I think they used Youth Brigade or something. But that was around ’84.

Well, when you mentioned the Suburban Lawns, just the name of it… It seems that in California the punk scene – especially the second wave, the Adolescents and bands like that – along with the skateboarding scene. That all came out of these suburban places. Do you think that plays a special role in how things developed?

Well, when you mentioned the Suburban Lawns, just the name of it… It seems that in California the punk scene – especially the second wave, the Adolescents and bands like that – along with the skateboarding scene. That all came out of these suburban places. Do you think that plays a special role in how things developed?

LM: Well I think anything out of L.A. is suburban. There is no downtown L.A. Every city is suburban, no?

SA: Suburbia is a thing that didn’t have to do anything with anybody at that time. It was more a label thing. It wasn’t ever a conscious thing. Some bands like The Descendents made fun of it. Suburbia is a theme in some of their songs.

So, you grew up in the suburbs, too?

LM: I grew up in East L.A, which is very… cholos. It was Mexican gangs. I lived right on the border of this very rich area but I was light years away from these skateboarders. I could skateboard to downtown in about 40 minutes but I thought I lived five states away from Hollywood when I was a kid.

SA: Where we lived the beach was how far away: 35 miles at least, 40 miles. We were definitely inlanders, and I always wanted to go to the beach but my mom and dad hardly ever took us. We’d go to the beach in the summertime maybe once a month. But I craved going to the beach. And I wanted to be a surfer. So, the closest thing to surfing was skateboarding – at least for me.

LM: I can say the same for me. I craved to be a skateboarder but I had to go to Montebello Skate Park. Montebello was the sad dwarf cousin of every skate park. It was outdated when it opened, while these guys were riding15 foot bowls.

SA: Yeah, our skate park [Upland?] was the first vertical skate park. It was gnarly, insane. Looking back now, I’m just stoked we got to skate that stuff. That’s where I learned. It’s pretty much the gnarliest skate park ever built, really, in the old days. At least old day skate parks.

When was that built?

SA In 1977. It lasted from ’77 to ’88.

Why did they close it?

SA: For insurance purposes. Couldn’t keep it afloat cause the economy was bad, too, at that time.

LM: Skateboarding was gone. Nobody skateboarded. A lot of the skate parks were pretty unsupervised. It’s a bunch of 13 to 18 year old kids basically at a summer camp on their own. It was a pretty high level of chaos and I think that the shows were just another place for that to happen even more extreme. Those early shows were pretty unsupervised. Anything could happen. There came a time in L.A. when they would not have punk shows any more, ever. Around The Decline of Western Civilization showings it was riots. Constantly.

SA: There was a riot at Santa Monica Civic, too, where ____ – I got to say this to get the whole thing – I was sitting right there when it happened, dude. He threw a beer bottle at a police car, right through the windshield. And then he got another beer bottle and threw it through the big old window of the front of the Santa Monica Civic. I was in the middle of pretty much every major riot that happened in L.A.

LM: It got to the point where the cop cars would just get lined up.

SA: First it was the weird art freaks, and then the skaters were mingling and then after the skaters got out, it was friends of skaters and then other weird whatever guys – and it was all those dudes that started the gnarliness. All the fights, the riots. It was unsupervised shows, there was hardly any security. It just e xploded, until the cops and the people just couldn’t take it anymore.

xploded, until the cops and the people just couldn’t take it anymore.

So how did skate parks fit into this? If you think about it, in terms of punk, you would think that skateboarders would say, “I don’t care about a skate park.” Because it seems as if it concentrates skaters where people can control them.

It was totally different than now. All the skate parks before were privately owned. A doctor and his son wanted to skate so they built a park. In the beginning they were trying to make them into realistic things but that didn’t work so they just became these empty wastelands and kids basically running themselves. They weren’t a controlled space.

Think about the alley in the back of the school where all the guys would go smoke and sniff glue. Oh, here’s the alley behind the school to smoke glue? That’s the skate park thing. Here’s our little place. We get in here, we control ourselves, no one comes in here. All sorts of chaos can happen. Everyone had bands upstairs. It was a club house. Totally different! Just a different time. I mean, there was two kids out of every city skateboarding that’d meet up so at the skate park there’s 15. Skate parks got really dead at the end of the 1970s. By 1980, they were dead.

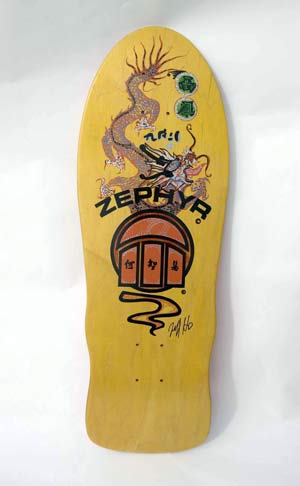

Jeff Ho was the first person I interviewed and Lucia Griggi photographed for this book. This was way back in the spring of 2009, when I was working on a couple of other books and was too frazzled to be doing anything right.

Jeff Ho was the first person I interviewed and Lucia Griggi photographed for this book. This was way back in the spring of 2009, when I was working on a couple of other books and was too frazzled to be doing anything right.

Okay we got ahead of ourselves. Let me go back and ask some foundation questions. Did you start skating first or did you start surfing first?

Okay we got ahead of ourselves. Let me go back and ask some foundation questions. Did you start skating first or did you start surfing first?

I started skating first.

What year?

In the Fifties. I was a metal wheel guy. And that one board you have a photo of was for the mid-sixties. I used to skate Revere with that. So when they talk about skating the banks, and surf/skate emulation, you know, we were doing that back in the Sixties. But we didn’t have the urethane wheels. Now when the urethane wheel came out, that gave you so much grip and made the ride so much smoother you could run over stuff easier and faster.

Faster.

And faster.

A lot more fun.

Well yeah it was like the grip. You still had the same loose ball bearings but that wheel gave you the extra grip that you needed to start turning quicker and do maneuvers and not slide out. With clay, chunks of the wheel would fall off, or you would hit like a little pebble and stop. But with the urethane wheels you could roll over that stuff and it gave you an advantage.

World of difference.

A World of difference.

Okay I started to write a long caption for you but it sucks and sounds like Wikipedia. Let me read that to you and you can breathe some life into it.

Go.

In 1973 Jeff Ho, Skip Engblom and Craig Stecyk opened the shop, “Jeff Ho Surfboards and Zephyr Productions,” on Main Street in Santa Monica.

In 1973 Jeff Ho, Skip Engblom and Craig Stecyk opened the shop, “Jeff Ho Surfboards and Zephyr Productions,” on Main Street in Santa Monica.

See the part I have problems with is Skip Engblom and Craig Stecyk. Stecyk is cool but Skip should have no credit.

Okay.

Go on…

In 1975 the young surf team members asked Ho and Engblom to start a skate team separate from the surf team. Cahill, Pratt, Adams, Sarlo, Peralta and Alva were the founding members.

They didn’t ask me to start the skate team, I just started it. I have to give you some backstory.

That is what I need.

Okay this is the real story. I bought the shop. It was my money. I financed it. Those guys want to take credit for it. That’s not right. And they’ve done it and all the articles, all the movies, all that crap. Everybody is taking credit for stuff that I did, and it doesn’t sit right with me. It was my money. I started the shop. I actually bought the shop from – what’s his name – Phil Castagnola. Because it was Select Surf Shop and I used to sell his boards out of the shop. Before I met Craig, before I met Skip, before I met any of those guys I used to work out of this shop and sell boards to Select. I bought the shop from Castagnola. I was on my way out… to Hawaii.

When was this, what year?

I can’t remember, but it was early 70s – ’71 or 72.

Why were you headed for Hawaii? For better waves?

No I was going to buy a piece of land. I had money to buy land and it was like five grand for an acre. And I was just going to go over there…

Oahu, or..

Either Oahu or the Big Island, it didn’t matter. I was just going to get myself some land.

Are you from Hawaii originally?

No I’m from California. From the Santa Monica, LA, Venice, Culver City area = West LA. I’ve surfed on and off at these beaches since I was a kid. A very very young kid.

So it was you that started Jeff Ho Surfboards and Zephyr Productions and it was you that started the skateboard team.· Then it reads: “Cahill, Pratt, Adams, Sarlo, Peralta and Alva were the founding members. Soon after, the team grew with the addition of local skaters Bob Biniak, Paul Constantineau, Jim Muir, Peggy Oki, Shogo Kubo and Wentzle Ruml.

So it was you that started Jeff Ho Surfboards and Zephyr Productions and it was you that started the skateboard team.· Then it reads: “Cahill, Pratt, Adams, Sarlo, Peralta and Alva were the founding members. Soon after, the team grew with the addition of local skaters Bob Biniak, Paul Constantineau, Jim Muir, Peggy Oki, Shogo Kubo and Wentzle Ruml.

Yeah but, you know… before those guys we had John Baum. We had the Tavares brothers, we had Craig Freebairn. On and on and on and on.· There’s so many names that they just left out of this whole deal, and it’s kind of disgusting. The way that the played it. The way they used stuff that I did and put a spin on it.

You say “They.”

I mean “they,” dude. There’s some crap in these magazines… interviews that these other people have done, talking about boards and who did what and who did this and how they named that or whatever. Craig Stecyk was the artist, the journalist, the photographer, the intellectual. What have you.

He was the media brains of the operation.

You’ve got to give him credit, because Dogtown was his name. He made the Dogtown. There are some other people trying to take credit for coming up with that name. It was all Craig Stecyk.

Do you still get along with Stecyk?

Yeah.

Stacy?

You know what? I don’t know what Stacy does. Stacy… God bless him he is in his own world. But you know what I am trying to do it is correct some of the things that have been mistaken in the media.

That’s what this is for. That’s great.

There are so many rumors and so many stories that aren’t true. Whatever. I mean, you go “whatever” and you want to move on. Just move on, but some of it is….

It gnaws at you.

No it’s repulsive, is what it is.

Okay.

And it does a disservice to the people who are really fans. They deserve to know what the real truth is. They don’t need to know some… some fantasy. That is why they called that one movie a “docudrama.” And the other was a fiction.

Okay so now my increasingly bad intro reads: “Engblom would coach them and insisted on high performance and good style. Bicknell Hill at Santa Monica beach was the main practice area for the team.”

Okay so now my increasingly bad intro reads: “Engblom would coach them and insisted on high performance and good style. Bicknell Hill at Santa Monica beach was the main practice area for the team.”

No.

No?

Okay… what happens is.. Skip used to sit inside the shop. I used to bring these guys out here in this parking lot, right here, and we used to have team meetings. I’d ask them to practice and show me their new trick. Anybody who runs a skate team knows the guys you have on the team have to practice. They have to learn new tricks, otherwise what’s the point? They’re supposed to be promoting the brand. Even today team managers are asking their guys: “Well are you learning new tricks?” And their job is to learn new tricks, and to become better and to win.

We used to practice here in the parking lot behind the old surf shop and also in the parking lot of Star Liquors. They had more pavement across the street. We also practiced in the middle of Bay Street. And the downhill slalom courses· we used to run at Bicknell.

At night? Can’t see you putting slalom cones on Bicknell in the modern world. You’d have the SWAT team on you.

No, we would just do it during the day. Wednesday was our team meeting day. Team practice. There’s a lot of misconceptions about the team, you know.

The Zephyr team.

The team was a surf team in the beginning. Nobody was doing any skate contests. Skateboards were used as transportation.

There was no organization.

There were no organized functions. You asked who should be included in this book. You’ve gotta go to Bill Bahne, you know. He did fin boxes and he did fins. I used to go down there and buy fins and boxes from him.

We took portraits of him in Encinitas and I think he has been in that one spot all along.

Down to Encinitas. He’s got a factory down there. He’s still down there. Still doing fins. He came up TO LA? and got a bunch of material and he came up with the fiberglass skateboard. And so they started using the extruded glass and the Chicago trucks and they got the wheels from Frank Nasworthy and that’s really how the whole situation started.

Bill Bahne.

I’m giving Bill Bahne the credit. He’s the guy who kind of major league started this – the distribution of the urethane wheel to more of a mainstream thing.

One day I go down there to pick up some fins. Bill shows me a skateboard and says “Hey you know check this thing out.” So I rode one and I said “Well give me a couple of those and I’ll take them up to the shop and see how you go.”

What year do you think this is?

I can’t remember. It was in the Seventies, you know. He was using the Cadillac Wheels. We brought the wheels up here, and then it was on. They started having skateboard contests, and Jay Adams was the first to go to some of the skateboard contests because his folks took him. He was on the surf team.

Yeah, the Zephyr/Jeff Ho Surf Team. He was riding for me. I’ve known Jay since he was a little grom. One of the first times I met him he paddled up to me in the water and he goes “Are you Jeff Ho?”· And I go “Yeah, who are you?” And he says, “I’m Jay Adams.” And he’s riding this really little board and he goes, “Yeah my dad works for Dave Sweet.” I said, “Dude, all right.”

So as the years went by I got to know him and put him on the surf team. And you’ve gotta give it to Jay Adams. He was one of the first guys to go skate contests. So we started sponsoring some of the guys that surfed and getting them to the skate contests.

When I talk to others about the Bahne-Cadillac contest in 1975, you will hear some rather loud raspberries about the way that contest was painted – and the Z Boys influence there.

Well it was a pinnacle deal. During that time period in ’74 and ’75 when the transition was taking place more skateboard contests started showing up at these fairgrounds: Orange County, Ventura and then they did Del Mar. Again, Bill Bahne was responsible for that. Sponsoring that contest. He put that contest up. The Bahne/Cadillac.

A lot of people don’t give Bill credit. He was responsible for a lot.

Tony Hawk’s first board was a Bahne. He’s one of those guys who has an engineering background and he has always been an innovator and trying to innovate something for the surfboard.

Okay we were talking about the Del Mar Nationals. This is what I wrote:· “This was the first major skateboard contest since the original skateboard heydays of the mid 1960’s. Jay Adams was the first and the youngest to compete and then the rest of the Dirty Dozen backed him up. At the end of the competition, half of the finalists were members of the Z-BOY crew. The results were: Women’s: Oki 1st, Junior Freestyle: Adams 3rd, Alva 4th, Junior Slalom: Harney 2nd, Pratt 4th. The older skateboard establishment was not ready for the aggressive surf style and free spirited approach that the Z-Boys exhibited and could not comprehend that they had just witnessed a revolution. The popularity of the Z-Boy style with vertical and airborne moves would sweep around the world.”

Okay what’s also wrong is we’re leaving Tony Alva out of this. Tony Alva was an integral part of the surf/skate movement. He was a little bit older than Jay and he had the drive. He had the edge and he was really highly self-motivated.

He was just motivated and I don’t know whether it was money or pride or what, you know? He was just self-motivated. He wanted to be good at something and I guess skateboarding was it – one of his tickets. He was a good surfer back then and he did win contests and stuff.

Jay flowed. Jay could flow and he had some natural ability but Tony took it up a notch because he had that edge – the motivation or drive to become better or the best in the world.

Yes I read that a lot about Tony and when you read the results in all the skateboard contests in the 1970s, he was up there like Kobe. Always at or near #1.

He was always doing stuff and getting his board to go faster and doing big big maneuvers. So it was no question that he was going to be one of the best in the world, whether it be speed-skating downhill, going the fastest or launching the biggest air. Tony’s just got this mad dog… Tony the mad dog. That is how he gets his nickname.

He was just so explosive when he skated. It wasn’t like he did some tricky move or whatever, a little pirouette. Whenever Tony did something it was always bigger and faster than everybody else.

Let’s see here. Baloney baloney baloney. But then it goes: “Jeff Ho still shapes surfboards and makes skateboards from his warehouse in Santa Monica.”

I’m inland, but call it like Venice.

I thought this was Venice?

I’m not doing them here. I have another place. Well kind of Venice/Marina Del Rey. Right in that unincorporated area.

Okay so now it gets into the bad interview we did before. I ask: “Why Zephyr?” And you say, “Why Zephyr? Zephyr is the god of the west wind. It comes from Greek mythology, ya know? Greek mythology and the symbol of the waxing crescent moon.”

Waxing crescent moon.

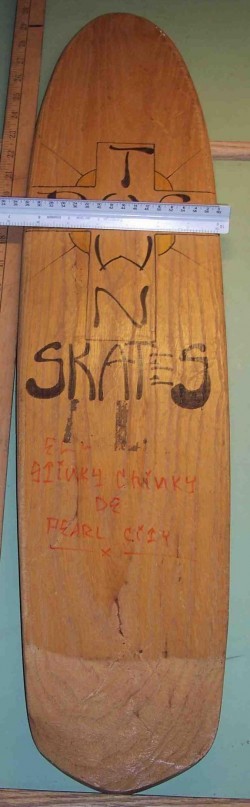

I asked: “What is the oldest board here?” and you said, “This is that one, the Revere one.· This skated Paul Revere Junior High, back in the day, in the sixties, when I was a kid. I was a skater before I was a surfer.” But that is not your first skateboard?

No. My first was custom made and had Metal wheels.

Just a chunk of wood with metal wheels?

Just a chunk of wood with metal wheels?

A little flat piece of two by four or one by six. Some of the boards back then were a little wider. I had that with Chicago skate metal wheels. When I was a kid I was small, and I used to bomb a hill at Hauser and Pico. When I look at it now, it’s a little bump. But when I was a kid, on metal wheels, that was the fastest, biggest hill I knew of. We also used to bomb Tuller Hill in Culver City.

And then I say, “I want to know what genius put that perfect terrain at a junior high school in Los Angeles.” And you say: “I don’t know dude. Paul Revere has been around for decades. It was there before we found it and it was virgin, ya know?” So what about Paul Revere. People were there before you, do you think?

I don’t really know who was the first person to skate it. The Hiltons and that group used to skate it, and we found it in the 1960s. But we called it Ranch Road, because old Ranch Road comes right down from Benedict Canyon right into where the baseball field used to be. It’s like a wave. I just know that I skated with a bunch of guys and we used to go up there and climb the fence on Saturdays and we’d go.

Was this the 50s?

It had to be the 60s. The early to mid-60s.· With Chris Dawson. You see, here’s another thing they don’t talk about: Chris Dawson.

Chris Dawson taught Stacy Peralta how to do these 360s and the moves that made Stacy famous! The nose 360 and the tail 360. Those were all moves that Chris Dawson did when he was on the Hobie team, back in the 60s. We brought some of that 60s influence into the 70s. But there’s no mention of Chris Dawson anywhere.

Well he gets some credit in this book. I interview him during what I call The Dark Ages, between 1965 to urethane.

Well that’s good.

So this wood board was your Paul Revere Special?

These are the Hobie Super Surfer wheels. I put these on in about 1968. I got them from Jay Stone and he must have got them from Hobie Vita-Pakt. This was probably the last set of wheels I had on this. There’s probably been about five sets of wheels on this board.

Now what about this board? I remember these boards from the 1970s. If the material polypropylene?

This board here was put together and made in this shop and I screened it in the shop down at the end of the street. And there’s probably about twenty of these made. This one had the um, color coat on top of it.

It’s fruity. Makes me want to lick it like that Willy Wonka wallpaper. This is like an old crap one I had laying around. The big long one is an old one. They’re all old. Oh, that one is a template from the seventies.

That one, the blue one is like the competition team logo, and all that. That’s a team board. This board has a 70s outline as well. I had many surfboards that had that outline.That was like…and these are templates back from the late seventies when boards were starting to evolve.

Now, these are like…I found these when I was just looking around but these are some of my templates… this is from seventy-eight. And then these are, I don’t know…ones a narrow tail, this one’s a wide tail. Ya know, they’re kinda…this ones a thirty-two, ten-and-a half. This one was six-nine, seventy-eight. Yeah, so these are some old templates and stuff.

…These ones are likes classics from the period. This is like a hand-painted one. This one has been in storage since eighty-five or eight-six. What year is it? Over twenty years.· And this one, so that’s how mint condition that one is, in the original wrapper and stuff. I did that one when I was up in West LA. This one here is something. This is an original board from seventy-five and this was a different process from some of the other ones. This is one of the boards that we hand-screened. Ya know? So there’s probably only like twenty of these.

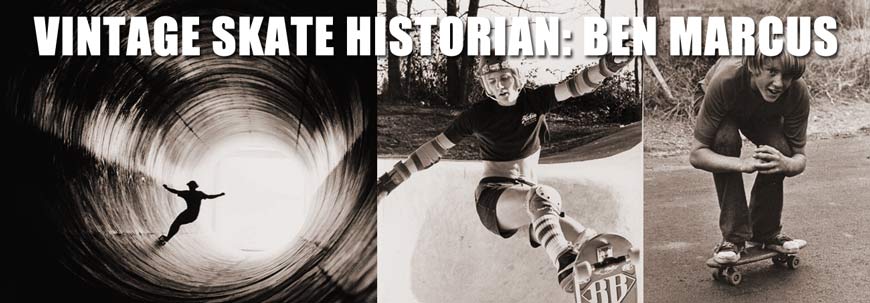

Story By Ben Marcus from The Good The Rad and the Gnarly

Photos by Lucia Griggi

The many faces of Steve Caballero and friends. Cab is a classic case of a skate park kid made good. Born in 1964 – the Year of the Dragon – Caballero utilized the dragon theme in his graphics, as he became one of the leading skateboard stars out of the 1970s and into the 1980s. He started off riding BMX inspired by Evel Knievel – a major cult hero of the 1970s. He began skateboarding at the age of 12, just goofing around, when just making the turn from the driveway to the sidewalk was a big deal. A big fan of comic books and monster magazines, skateboard magazines also caught Caballero’s fancy and inspired a deeper interest – beyond the driveway. Caballero became a teenager just as skate parks were sprouting up around the world.

The many faces of Steve Caballero and friends. Cab is a classic case of a skate park kid made good. Born in 1964 – the Year of the Dragon – Caballero utilized the dragon theme in his graphics, as he became one of the leading skateboard stars out of the 1970s and into the 1980s. He started off riding BMX inspired by Evel Knievel – a major cult hero of the 1970s. He began skateboarding at the age of 12, just goofing around, when just making the turn from the driveway to the sidewalk was a big deal. A big fan of comic books and monster magazines, skateboard magazines also caught Caballero’s fancy and inspired a deeper interest – beyond the driveway. Caballero became a teenager just as skate parks were sprouting up around the world.

His first experienced was at Concrete Wave Skatepark in Anaheim – during trips with dad to Disneyland.· Closer to home, Caballero became a regular at the Winchester Skate  Park in Campbell and then bailed on Winchester for the Campbell Skate Park – because it was only $1 a day to skate. Caballero competed with the Campbell Skate Park team. He had a natural talent and a driven enthusiasm – because skateboarding was something where a little big man could excel. Stacy Peralta saw that excellence early on, and Caballero became one of the first team members for Powell Peralta in 1978 – at the age of 14.

Park in Campbell and then bailed on Winchester for the Campbell Skate Park – because it was only $1 a day to skate. Caballero competed with the Campbell Skate Park team. He had a natural talent and a driven enthusiasm – because skateboarding was something where a little big man could excel. Stacy Peralta saw that excellence early on, and Caballero became one of the first team members for Powell Peralta in 1978 – at the age of 14.

By 1980, Caballero was already a veteran of skate park bowl competitions and he had christened his own trick: The Caballerial, aka a fakie 360 ollie. The Half Cab is a fakie 180 ollie. Into the 1980s, Caballero was one of the star members of the Bones Brigade, featured in the series of action sports videos produced by Stacy Peralta and Craig Stecyk for Powell-Peralta. Steve Caballero was one of the major skateboard stars of the 1980s, and he surprised himself and his parents by earning a very good living with board sales and shoe sales. One of his better qualities is that he is very loyal to the companies who first sponsored him.

Thirty years later, he is still with Vans and Powell-Peralta. This portrait was taken in the winter of 2010 at Caballero’s home in Campbell, where lives surrounded by comic books and superheroes with his wife Rachel, daughter Kayla, revved-up son Caleb and two protective dogs.

Photos by Lucia Griggi

The answer is: We may never know. Many inventors and corporations are quick to stake a claim, but finding that first commercially produced skateboard may be a futile search. In the first edition of the Quarterly Skateboarder, a full-page ad by Skee Skate of California makes a heavy claim: “This is it!!!! The skateboard that started it all.” Others begs to differ. Many historians and collectors believe the eponymous skateboard launched by the Roller Derby Skate Corporation was the first mass-produced skateboard. It well may be, although no one is certain when it was launched.

The answer is: We may never know. Many inventors and corporations are quick to stake a claim, but finding that first commercially produced skateboard may be a futile search. In the first edition of the Quarterly Skateboarder, a full-page ad by Skee Skate of California makes a heavy claim: “This is it!!!! The skateboard that started it all.” Others begs to differ. Many historians and collectors believe the eponymous skateboard launched by the Roller Derby Skate Corporation was the first mass-produced skateboard. It well may be, although no one is certain when it was launched.

The Roller Derby was a wooden plank with a rounded tip at one end and modified roller-skate steel wheels attached. It boasted no concave or even kicktail, no mention grip tape, but it did have a snazzy bright-red paint scheme. Many believe the Roller Derby made its debut in 1959. But the company itself claims it introduced the board in 1963. David Kennedy, Roller Derby’s current vice president and CFO in Bottoms up views of the Humco Surfer which got all high tech with a spring loaded suspension. Humco courtesy G&S. Litchfield, Illinois, responded to this important query by producing a nine-page Roller Derby skateboard promotional brochure—first published in 1964.

The Roller Derby was a wooden plank with a rounded tip at one end and modified roller-skate steel wheels attached. It boasted no concave or even kicktail, no mention grip tape, but it did have a snazzy bright-red paint scheme. Many believe the Roller Derby made its debut in 1959. But the company itself claims it introduced the board in 1963. David Kennedy, Roller Derby’s current vice president and CFO in Bottoms up views of the Humco Surfer which got all high tech with a spring loaded suspension. Humco courtesy G&S. Litchfield, Illinois, responded to this important query by producing a nine-page Roller Derby skateboard promotional brochure—first published in 1964.

Jim Scheller was Roller Derby vice president at the time. He began working for the company in 1957: “I don’t recall any skateboards in 1959. I believe that the first skateboard production for Roller Derby was in late 1963 and the beginning of 1964. The idea came from California, where we had a warehouse managed by a guy named· Sloniger. We did a little retooling at the plant in Litchfield but not much, and it turned out to be a good· business. Very good.” While the Roller Derby may not have been the first commercially produced skateboard, it was likely the first mass produced board, as many of them survive today.

Written By Ben Marcus: The Good The Rad and the Gnarly

Still, other skateboards may have arrived earlier. Historian Iain Borden claims in his Skateboard, Space and the City: Art and the Body (2001) that 1956 was the first year: “The first commercial skateboards—like the Humco five-ply deck with ‘Sidewalk Swinger’ spring-loaded trucks (1956), the Sport Flite, and the Roller Derby (late 1950s to early 1960s)—came with steel wheels around 50mm in diameter and 10mm wide.” In his book Skateboard Retrospective: A Collector’s Guide, Rhyn Noll points out a two-wheeled contraption from the 1930s owned by Randy Beck from Chatsworth, California. This machine has two wheels attached to a piece of wood, but if we’re using the strict definition of four wheels and two trucks, this doesn’t quite fit in.

Still, other skateboards may have arrived earlier. Historian Iain Borden claims in his Skateboard, Space and the City: Art and the Body (2001) that 1956 was the first year: “The first commercial skateboards—like the Humco five-ply deck with ‘Sidewalk Swinger’ spring-loaded trucks (1956), the Sport Flite, and the Roller Derby (late 1950s to early 1960s)—came with steel wheels around 50mm in diameter and 10mm wide.” In his book Skateboard Retrospective: A Collector’s Guide, Rhyn Noll points out a two-wheeled contraption from the 1930s owned by Randy Beck from Chatsworth, California. This machine has two wheels attached to a piece of wood, but if we’re using the strict definition of four wheels and two trucks, this doesn’t quite fit in.

Noll also mentions a Mr. Carl Jensen: “I hear tales of Mr. Carl Jensen in the late fifties, a man who built early skateboards and brought them into my dad’s shop, Greg Noll Surfboards. Greg recalls Mr. Jensen as the first to sell skateboards to his Hermosa Beach shop in 1958, and considers him a founder of the commercial skateboard.” The book also points to 1958 as the year A. C. Boyden “better known as Humco, patented one of the earliest recognizable skateboards.” Looking through the collections of Todd Huber, Paul Naude, Gordon & Smith, and others, there are numerous odd-looking skateboards—some made of metal, some made of wood—that seem to have come out of the 1950s. There are boards by the Chicago Roller Skate Company, and it would make sense that it would be among the first to manufacture a skateboard, as it was one of the Big Four that controlled roller-skate production in the 1950s.

So which came first? Skee Skate? Roller Derby? Chicago? Humco? Or that Carl Jensen chap? I talked with Greg Noll, who made a good argument that Carl Jensen was the first guy to make a commercial· skateboard—and Noll himself may have been there at the start as well. Now, I don’t really care about this all that much and I don’t want to go around claiming that I made the first commercial boards, but first of all, in the 1950s we called those board “bun boards,” because when you fell you were always busting your ass. I opened my first shop on Pacific Coast Highway across from Center Street School in Hermosa Beach. At the time there was this guy Jensen who had five or six guys rolling around on the strand on the north side of the Hermosa Beach pier, riding these boards that had old roller-skate equipment with steel wheels.

So which came first? Skee Skate? Roller Derby? Chicago? Humco? Or that Carl Jensen chap? I talked with Greg Noll, who made a good argument that Carl Jensen was the first guy to make a commercial· skateboard—and Noll himself may have been there at the start as well. Now, I don’t really care about this all that much and I don’t want to go around claiming that I made the first commercial boards, but first of all, in the 1950s we called those board “bun boards,” because when you fell you were always busting your ass. I opened my first shop on Pacific Coast Highway across from Center Street School in Hermosa Beach. At the time there was this guy Jensen who had five or six guys rolling around on the strand on the north side of the Hermosa Beach pier, riding these boards that had old roller-skate equipment with steel wheels.

Jensen brought them to the shop and said, “This is going to be a good thing.” Well, I got so tired of hearing all this BS, but I put a couple in the showcase and they sold. So then I started making some outlines and laminating them and I had a rubber stamp that said “Greg Noll Surfboards,” but all the time I was thinking, “These things will never sell.” I sold maybe fifty of the boards over the course of a year, but I didn’t really see the potential in it and as usual I was left standing at the train station as the train was pulling away, because then Hobie and Makaha and Gordon & Smith came along and of course they sold millions of the things—everyone’s making a bunch of dough.

I don’t have one of those original Greg Noll stamped skateboards and I wish I did. But just this year Element came out with a special edition of those bun boards, and they look pretty much the same as what we were making back there in the late 1950s, early 1960s. So am I the first guy to make a commercial skateboard? I don’t give a damn. All I know is, a lot of guys got rich from something I didn’t think was going anywhere.

Cred is important in skateboarding,so let me establish mine. I began skating when I was ten in sunny California around 1970, in the bad old days of clay wheels. I also started surfing about then, walking with my purple Haut longboard every day from Santa Cruz’ Seventh Avenue to Cowells, and putting in the time to learn the secrets of the sea and suffer the slings and arrows of learning to surf. In California in the 1970s, surfing and skateboarding went hand in hand: if you surfed, you skateboarded.

Cred is important in skateboarding,so let me establish mine. I began skating when I was ten in sunny California around 1970, in the bad old days of clay wheels. I also started surfing about then, walking with my purple Haut longboard every day from Santa Cruz’ Seventh Avenue to Cowells, and putting in the time to learn the secrets of the sea and suffer the slings and arrows of learning to surf. In California in the 1970s, surfing and skateboarding went hand in hand: if you surfed, you skateboarded.

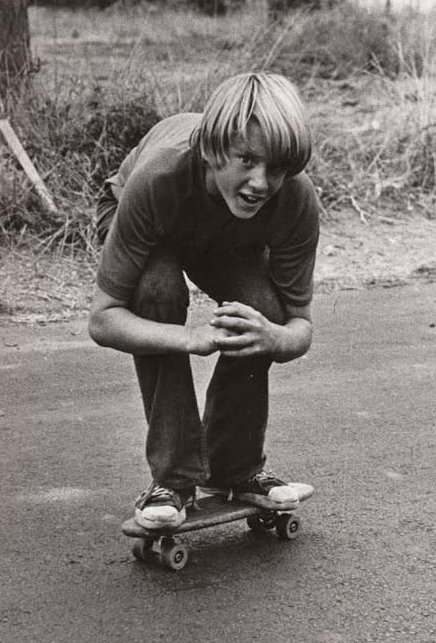

Ben Marcus, circa 1975, styling on a Hobie Super Surf with composition wheels in good old Santa Cruz, California. In school they would sometimes show surfing and skateboarding movies, and that’s where my friends and I were introduced to SkaterDater. For our generation, it was a life-changer.· Here were a bunch of skater kids going berserk over a movie about other skater kids. My friends talked about SkaterDater for months later— about how cool it was that these kids could hop curbs without their feet leaving the board.····· Look for Ben’s latest Book “Skateboard”

I feel lucky to have grown up in Santa Cruz at that time, in part because I was around for the transition from clay/composition wheels to urethane wheels. This happened around 1973, and like everyone who read Surfer magazine, I was mesmerized by images of Gregg Weaver with his long blond hair, contorting himself into positions on his board that were scarcely to be credited. Although the photos were stills, it was obvious that Weaver was hauling ass on his board, and torquing the wheels into positions that would surely have resulted in· crash on clay wheels.

Clay wheels were Flintstones’ technology; urethanes were pure Jetsons—the future. The wheels whirred like a spaceship, and made you feel like you were barely in contact with Earth’s surface. It’s hard to appreciate just what a big deal urethane wheels were, but my friends and I went nuts—as did the skateboarding world. My buddies Alex Johnson, Michael Duffy, Danny Ford, David Wampler, William “Winki” Thurlow, and I skateboarded all over Santa Cruz. There were long hedges to duck under for tube rides and lots of sidewalks leading up into driveways where we could do flowing, swooping, 1970s-style surf turns. It was simple fun, but it was fun. The best skater in our bunch was Kevin Reed, arguably the most innovative surfer-skater around Santa Cruz at the time.· He was tall, thin, and about twenty years ahead of his time. I remember him skateboarding a drainage ditch that some called the Pit and others called the Dip, depending on what side of town you were from. He was fast and graceful and made it look good.

At some point, I helped Kevin finish a high school history paper, and he returned the favor by taking a photo of me riding one of his King Kustom Kazar boards with Cadillac Wheels, skateboarding a place on the west side of town called Liptons, because it was right across from the Lipton Tea factory. Somehow that photo ended up on the back cover of one of the first skateboard books of the urethane era, ·Anybody’s Skateboard Book.

At some point, I helped Kevin finish a high school history paper, and he returned the favor by taking a photo of me riding one of his King Kustom Kazar boards with Cadillac Wheels, skateboarding a place on the west side of town called Liptons, because it was right across from the Lipton Tea factory. Somehow that photo ended up on the back cover of one of the first skateboard books of the urethane era, ·Anybody’s Skateboard Book.

I graduated from high school in 1978, and that’s pretty much where skateboarding ended for me and a lot of my friends.· As I researched this book and talked to other skateboarders, that seemed to be the pattern. You start skateboarding as a kid, get really into it as a teenager, have a blast with your friends through high school, and then all that enthusiasm is dispersed after graduation—by college, commitments, age.

My skateboard cred starts to fade after the 1970s, even though I worked at Surfermagazine for ten years, most of that with Steve Hawk, brother of· Tony. ·At some point in the early 1990s, I visited Tony’s house in Fallbrook, where he had an epic backyard ramp set up. It was then that I witnessed firsthand how far skateboarding had come.

Bucket Brigade at Buena Vista pool out near Watsonville, in the 1970s. That pool was recently uncovered and has gotten more ink than a San Quentin lifer. Danny Digirolamo

·I’ve written nine books on various aspects of surfing, but this book is by far the most difficult and time-consuming book I have ever done. I knew I was in trouble when I walked into Larry Balma’s barn in east Oceanside and saw the hundreds of skateboard magazines and industry journals he’d collected and carefully saved over the years. If I sat there for four years I don’t think I’d be able to read it all.

But I pushed on, piecing this book together from books, videos, and online articles, and interviews with dozens of people, from 1940s skater Carl Knox to the Sector 9 guys at an ASR show today. Of all the resources I used for this book, two of the best for IDing skateboards were the Disposable books by Sean Cliver and www.artofskateboarding.com.

All told, there were probably twenty thousand distinct skateboard decks that have been made since the late 1950s. This book isn’t meant to identify the provenance of every·deck, wheel, truck, and accessory ever made, but to detail the “arc” of skateboarding—if· I can use a Hollywood term—and highlight the most important people, events, boards, and··innovations to show how skateboarding, began as a crude sport invented by surfers in the late 1940s, became a multibillion dollar industry and sport practiced by millions around the world. Perhaps even more importantly, this book celebrates all that simple fun my friends and I had skateboarding.

The skateboard was invented in 1956, by Marty McFly. It was all something of an accident, because just after the terrorists murdered the professor, McFly jumped into a DeLorean DMC-12 automobile that was also a time machine, powered by the Flux Capacitor. McFly made good his getaway by going back in time. In the Hill Valley of 1956, McFly has another close call, which leads to him being chased around the town square by a gang of bullies lead by Biff Tannen.

The skateboard was invented in 1956, by Marty McFly. It was all something of an accident, because just after the terrorists murdered the professor, McFly jumped into a DeLorean DMC-12 automobile that was also a time machine, powered by the Flux Capacitor. McFly made good his getaway by going back in time. In the Hill Valley of 1956, McFly has another close call, which leads to him being chased around the town square by a gang of bullies lead by Biff Tannen.

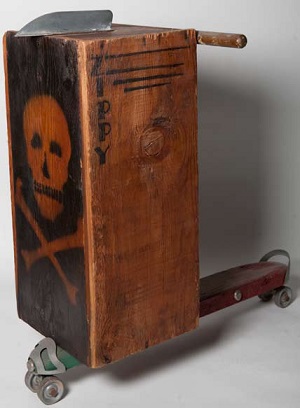

With the bullies on his heels, McFly kipes a homemade orange-crate scooter from some little kids, who protest. The scooter is not a time machine and McFly is not fast enough and the bad guys are gaining on him, so he kicks the handlebars and the flimsy crate from the scooter and voilà, the skateboard is born: a clunky piece of wood with roller-skate trucks and metal wheels. This crude skateboard works better than a scooter. McFly does a couple of kickturns—the very first kickturns, but no ollies, et—then grabs the tailgate of a truck and escapes into history. And the kids who were protesting are now instant converts, the first generation of ’boarders.

The fiction of the 1985 Hollywood film Back to the Future has a basis in fact, although time travel was probably not involved. While the skateboard did evolve from the scooter and roller skates, that evolution began farther back in the 20th Century and even as far back as the 19th Century.·

There are two questions that drive most discussions about the early evolution of the skateboard: Which came first, the scooter or the skateboard? Did skateboarding exist in some form before 1940s surfers started stealing roller-skate wheels, nailing them to 2×4 boards, and riding their contraptions with no hands—no T-bars or fruit crates?·

Let’s take the first question: the truth is, a skateboard-like component is the foundation for all scooters, so well before 1956, kids and parents around the world were laying the foundation for skateboarding when they attached wheels to a short piece of wood or metal as the basis for a wheeled device called a kick scooter. The kick scooter is a skateboard ancestor propelled by the rider’s back foot. The front foot stayed onboard, and the driver steered with a handle attached to the front, over the wheels.

Let’s take the first question: the truth is, a skateboard-like component is the foundation for all scooters, so well before 1956, kids and parents around the world were laying the foundation for skateboarding when they attached wheels to a short piece of wood or metal as the basis for a wheeled device called a kick scooter. The kick scooter is a skateboard ancestor propelled by the rider’s back foot. The front foot stayed onboard, and the driver steered with a handle attached to the front, over the wheels.

The first known patent for a scooter is dated 1921, but the scooter goes farther back than that: it’s a form of locomotion that evolved from roller skates, which go all the way back to the late eighteenth century, when Belgian inventor Jean Joseph Merlin patented a method of wheeled fun that was actually more like a modern inline skate.