ALL THE YOUNG DUDES, ANNOYING ON PURPOSE, THE WILD ONES Steve Alba and Lance Mountain On the Origins of Inland Skate Heroes, and SkatePunk.

ALL THE YOUNG DUDES, ANNOYING ON PURPOSE, THE WILD ONES Steve Alba and Lance Mountain On the Origins of Inland Skate Heroes, and SkatePunk.

In the parking lot at Malibu during a south swell in August of 2010, Steve Olson said he wasn’t the Missing Link. I had told him I wanted to interview him for the end of Chapter Five of the skateboard book, because he was a major player toward the end of the 1970s, and I was hoping he would be the skater I was looking for – the first major figure who didn’t start out as a surfer. The guy who was the figurehead for what skateboarding would become in the 1980s – as Skateboarder Magazine folded and Thrasher started up, and skateboarding moved away from the sunny surf to the shady turf.

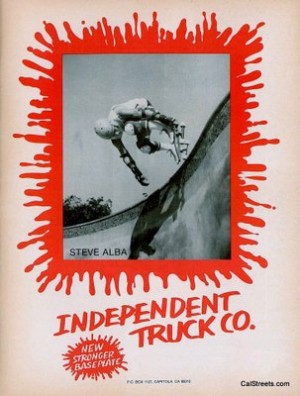

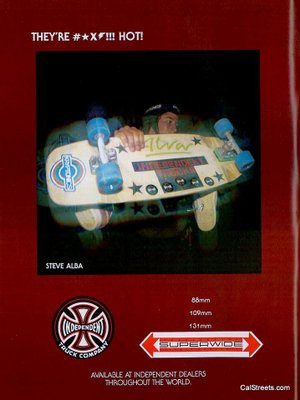

Olson said he wasn’t that guy, but Salba was. I knew we had a good portrait of Salba taken at the Vans skate park and I was going to contact him and then I remembered that curious German chap named Konstantin Butz who had emailed the California Surf Museum in Oceanside saying: “I am a Ph.D. student from Cologne, Germany and the working title of my dissertation is “The Californian Body in Rebellion: An Intersectional Analysis of Skateboarding and Hardcorepunk.” Basically, I deal with the phenomenon of skatepunk and its site-specific “origins” in suburban Southern California and the local punk and surf culture. In that, I focus on the body and body theories.”

Huh? And I thought I was weird.

But Julie Cox at the CSM sent Konstantin to me and I loaned him my pass to get into the Action Sports Retailer show in San Diego and pointed him in some directions I was only learning myself. Mo at Thrasher. Steve Olson.

And he returned the favor by letting me use his interview he recorded with Steve Alba and Lance Mountain at the Fontana Skate Park, on March 24th, 2010.

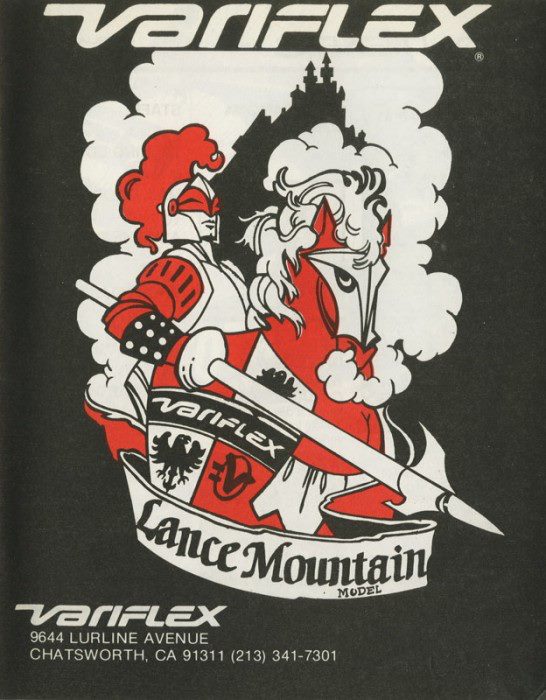

Mountain and Salba were two guys who came, from out of the east, in the late 1970s, with no surf connection at all. They were skatepark kids, who also were involved in the early days of punk.

These guys were the missing links, taking cutting edge skateboarding away from Led Zeppelin and Foghat and the bushy bushy blonde hairdos of the 1970s and into the jagged, bleached, safety-pinned 80s – with a whole new soundtrack: Blondie, Devo, Cramps, Dead Kennedys.

Steve Alba goes so far as to claim it was skateboarders who invented slam dancing. But these guys were my missing links. These weren’t surfers. These guys were inlanders. Skaters. Skate punks. And they lead skateboarding out of the 1970s and into the 1980s.

Konstantin: So why don’t we just start and talk about how you got into skateboarding and then also into punk rock: which was first?

Konstantin: So why don’t we just start and talk about how you got into skateboarding and then also into punk rock: which was first?

Well, I got into skateboarding first.

Which was when?

It was 1974, right around there.

How did you get into that? Did you grow up around here?

We’re in Fontana right now but I didn’t grow up in this area. I grew up west of here. Back in the day the Hell’s Angels ruled this place. You didn’t come out here unless you were a Hells Angel in those days. Well, Fontana, the city. Not the skate park. Fontana was gnarly dude. They used to advertise for the KKK on the 10 freeway in the 70s and I’m dead serious. I used to trip on that. They had a total KKK chapter out here.

So you grew up west of here?

Yeah, we grew up in Montclair, which was called the San Gabriel Valley and had a 714 area code. Now we’re the Inland Empire: Montclair, Upland, Ontario, Pomona, Claremont. I got into skateboarding because it looked cool and fun to do. My best friend’s brother skateboarded. He was the first guy that I saw… Gary Lazone was his name. Back in those days most guys were skating in a straight line. But Gary Lazone could do nose wheelies and tail wheelies and he could do a three-sixty and jump over a broom stick. Then he set up these slalom cones made out of Coke cans or whatever. This guy could actually skateboard, so we used to follow him around and asked him to use his board all the time and after a while he just got sick of us trying to use his stuff. We eventually got our own skateboards and learned to do all that stuff.

The street they lived on had a slight downhill angle, the sidewalk inclined and turned to the right or the left and there was a brick wall where the planters were. That was our way of learning how to go right or go left. We didn’t even call it frontside or backside. One thing led to another and we kept following this guy around and that lead to this alleyway called “Stoner Alley.” We were in sixth grade and we knew down that alley the Mexicans were at one end and the stoner kids were at the other end. They were always kicking people out and getting in fights so we were tripping out: “What’s going on down that alley?”

So Gary Lazone came through with this little buddies following. They jumped over this fence and we were: “What are they doing?”

So, we walked up to the fence but we didn’t jump over cause we couldn’t see them but we could hear them. We could hear that swoosh of pool skating. It’s a weird sound that is hard to describe but once you actually hear the swoosh of pool skating you don’t ever forget that sound.

We went back home but later that day we went back and jumped over the fence and checked it out and saw the little pool there. So, we start riding it, too: start halfway up and try to carve around deep end. That’s all we did.

Why was the pool empty?

This is the mid 70s and California had a gnarly drought going on. If your pool was empty you could not fill it up, because there was a law against it and if you used water, the water meter at your house would show you went through five, six thousand or whatever gallons it takes to fill the pool up. You’d get fined or even go to jail because that’s how serious the drought was.

We skated for a whole year before we got into pools – this was the spring and summer of ’75. After that our focus shifted away from learning nose wheelies and tail wheelies and three-sixties and jumping over broomsticks and going around Coke cans and going down hills and just all the basic stuff.

At that early point, did music play any role in skateboarding?

At that early point, did music play any role in skateboarding?

Well, back in those days, Gary Lazone was God. Not only did he skateboard, but he surfed, he boogie boarded, he played guitar. He knew how to play Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin and Foghat… Ted Nugent. Everything we were reading about in Cream Magazine, a rock magazine that had all these crazy bands on the cover. We started liking bands that looked really freaky and weird: Alice Cooper and David Bowie, and Iggy Pop was another weird dude.

We had no clue who they were but they were in Cream Magazine, which also covered glam rock and punk rock a little bit later. So we looked into the magazines and tripped on that and really got into Kiss and then the New York Dolls: “Who are those dudes?”

I think we were attracted to some whackness from the get-go. When we started skating the music at the contests was hard rock: Van Halen and Santana. But as skate style and music changed the New York Dolls started coming in and then New York City started coming in: the Ramones and Blondie and the Talking Heads and the Cramps all came out of New York. The music started getting crazier I still credit Steve Olson as the first guy to get into punk rock as a skater. He’s the guy that got people hooked.

How did he do that?

He just played this music. I’m pretty sure he saw Cream Magazine, too, but after a while we went out of our way to look for music. If there’s punk rock in New York, why can’t there be punk rock in California or England? At that time punk rock was the Sex Pistols and the Clash and it was all going on at the same time but we were still really little. In ’78 I was 15 so I was just starting to get into it. We hadn’t cut our hair yet. We started getting thrift shop clothes and you’d see Olson with a pair of crazy ass old man shoes that he spray-painted white and maybe put a pink stripe on them or whatever:

“Dude, what’d you do? Where’d you?”

“I just went to this shop, man…”

That was his thing but to this day I go to thrift shops, because you get the raddest clothes. So probably around ‘78, it started changing, and it was definitely Olson who was the first guy getting into it. Then it was me and after me it was probably Tony Alva. And after Alva it’s probably Duane Peters.

I wouldn’t say I’m a punk rocker now because I’m an old fart and don’t really dress the part but Duane’s definitely a true punk because he lives that style. , just out of control f#%@#% chaos – tornado all the time.

I just want a more stable life. I never wanted to stick needles into my arm either. I never got into that because I never saw the point. Why waste your time? But it’s trippy how punk rock and skating collided and bounced off each other for a while.

How did that happen? Why did that happen? How do they fit together?

As I see it, they’re both aggressive and full of do-it-yourself: You can’t buy it, make it. Cause we all did that in the old days: We made your own clothes. We got thrift store clothes and spray-painted them or put paint on them or put zippers on them. We copied England for a while. You like something and you copy it and don’t even really mean to; it’s a subconscious thing. It’s something in the styles you’re digging and that’s just human nature and that’s the seam of life. That’s how it works, man.

Lance Mountain was sitting next to us listening to the conversation. At this point he joins in. In the following Alba’s parts are marked as SA, Mountain’s parts are marked as LM.

LM: Skateboarding had reached this professional level in ’77, ’78, ’79, with guys like this guy here [Salba]. The guys before these guys really dug Led Zeppelin and that music but the next generation found their own music that fit what they wanted it to represent. I think a lot of skaters knew that they were into something that was really special but the world didn’t see it or care about it. And I think it just went hand in hand with punk: “Ok, I’m gonna make people see this. I’m gonna annoy them. I’m gonna show them and be seen.”

SA: I used to be annoying on purpose just to piss people off.

LM: They wanted to get under people’s skins, ‘cause they were really good at something only a hundred people in the world were doing. It was special and interesting but no one cared. They didn’t have big sports saying, “Hey, this is important,” so they went out and said… I know this cause where I went to school there were only one or two skaters and punks at school, and their whole play was different. They just let people know they were there. They didn’t want people to like them really. They just wanted to let them know that they’re there. That music and the skateboarding happened at the same time.

So, what environment was that to make them feel that?

SA: It was just anti whatever they had.

How did you grow up?

SA: Where I grew up we all played Little League and Pop Warner cause that was something to do in those days. Most of us did that. Montclair was a small town and we had only one high school, two junior highs and four elementary schools. So the people who I grew up with, from eight years old all the way until high school, they were all my friends and buddies, and when first I started skateboarding, they were, “Oh, whatever, this guy is…”

They didn’t give me too much trouble for it because it was that fad thing. You’re cool because you’re skateboarding. But when I started getting into punk rock, they just wanted to disassociate because it was different and it was weird and didn’t go with the flow and status quo.

At first I couldn’t understand why friends who I hung out with and who I played sports with wouldn’t trust me anymore and made fun of me. I tripped on it. It didn’t really hurt my feelings or whatever. I just figured it was me against you, us against them. They were jocks, we were punks. If they had long hair, we’d cut our hair short. If they wore flare pants we wore tight pants. If they wore whacky shoes we wore Converse or the weirdest, loudest shoes we could find. Everything we did was anti everything they did. We were different.

LM: Most of the early skateboarders were the goofy guys. They were more creative and interesting and then a few years later it became more a rebellious and violent thing. But at first skateboarding was for creative and artsy dudes. Olson wasn’t an aggressive angry, anti, violent dude. He was a creative, interesting dude.

The early punk bands were creative and interesting and then two or three years later they were the more aggressive football skinhead punks. In the beginning the skateboarders were more creative and quirky and that music… I remember, when I was young it was all Led Zeppelin but I used to hear a radio show called “Dr. Demento” and it was all this comedy music, – silly, funny music.

Dr. Demento played Devo and I thought: “This is an interesting band.” At the skate contests they’d play rock, rock, rock. Then I went to this contest and all of a sudden they were playing Blondie. Steve had a Devo shirt and I was: “That’s that band!” And pretty soon the skaters seemed to say: “Oh, that’s our music.”

SA: He’s right about… we were the younger guys. Skateboarding already had its established stars at that point. The Dogtown guys were the first guys, but once they kicked the door down a whole bunch of new guys came in. It was me, Steve Olson…

LM: It was a skate park thing.

SA: Yeah, it was all the skate parks.

LM: The early skateboarders were trying to make it an accepted sport, then these guys came along. The Dogtown guys did a lot of vert skating but supposedly you can’t judge it. I mean they never really had a vert contest for those dudes ever. And when they did, Steve won the first one. So okay, this is a new wave. This is a new way of doing things. That’s the same time I believe punk was getting…

SA: Definitely! It all happened simultaneously. The skaters before us had long hair and were surfer guys. They were cool – some of them were actually really cool. But at the same time they were really afraid of us because we were taking away what they had. That’s when pool riding came in; pool riding turned into park riding. And then later park riding turned into ramp riding. And then later ramp riding turned into mini-ramp riding and then street started to happen.

Did you use the term “skatepunk”?

Did you use the term “skatepunk”?

LM: No, that’s more …

SA: We didn’t use it. Originally, I think, it was just made up by Mo and the guys at Thrasher. Really more of a joke.

LM: That’s that second stage of punk. The original guys were into the dorky, arty music. That was a lot different than this second wave of aggressive skate rock.

SA: I’d say it began in 1978, so in ’79 and ’80 the first wave of guys was me, Alva, Duane. Then the second wave of guys when hardcore came in, it was different. Not to say that it wasn’t any better or any radder, cause it was alright. But I think the original punk rock was better. So, there was a first wave and there was a second wave.

So, could you compare that to what was going on in the L.A. punk scene? Because there you had X and the Germs and then you had Black Flag.

SA: Well I grew up with all those bands. The funny thing is, dude, we were kids coming in to watch all those bands. We were 15 when we first started going to the Masque [a pioneering punk club in Hollywood, which ran shows intermittently from 1977 to 1979]. I went to the original Masque, and there’s not a lot of people who can claim that. At first it was a very small group of people, and it was almost: “We’re hipper than all the other people.” I’ve seen every band L.A. had to offer probably at least eight to ten times. That was what we did, man. We just followed all the bands.

Were there bands who had a real connection to skateboarding?

I wouldn’t say that we were connected to skateboarding with those guys at all. They were aware of what we were doing because at the same time the skateboarders were the same guys that made up slam dancing. That was our version of Pogo – which was English. Slam dancing was our version of the pogo in California and it was me, Tony Alva, Steve Olson, Fausto Vitello.

When was that?

SA: This was in San Francisco in ’78 when we saw the Clash, Dead Kennedys and the Cramps.

LM: Instead of Pogoing vertically…

SA: …we just crashed into each other, man.

How did you come up with that?

SA: We wanted to get up on stage. ‘cause the Clash was gonna play and we wanted to touch the same stage that the Clash was on. The Clash was God, as far as punk rock bands go. The Sex Pistols faded, and let’s face it, the Pistols were rad on record but they sucked when Glen Matlock wasn’t with them.

I started playing guitar when I was 18, right around the same period. I was learning how to play and getting better and better as time went on. I paid attention to music and paid attention to guitar players and that’s why I was always trying to get up in front of the stage and would do it at any cost. In those days they didn’t have barricades. You got crushed. When we saw the Clash at that show, I’m telling you man, all of us, all we wanted to do was touch the damn stage that the Clash was on.

And that’s how you came up with the slam dance?

SA: Yeah, we were trying to get to the stage no matter what it took. We were drunk off our ass. We were drinking heavy. I’m not gonna say we weren’t cause we were. And all the other guys were probably loaded up on drugs. But yeah, it was rad. We’d climb over the crowd, dance to ourselves. I remember between the Dead Kennedys playing and waiting for the Clash to come on, we were so amped. It was energy. We just wanted to have more music.

And when the Ramones came out of the PA system between the Dead Kennedys and the Clash, we loved the Ramones at that time and we just started getting crazy and pulling each other down and hitting each other and tackling each other and sliding into each other and one thing led to another. We crashed into the crowd and the crowd started to get mad pushing back and we’re “F@#%@#% you!” and cracking the crowd.

I got in a fight with two big chicks and everyone was fighting with everyone and it was just nuts. Any time the skaters got together at any show, that’s all our deal was: get on stage. No matter what it took. And that’s how we started the whole deal.

Do you think it mattered that you were there as skateboarders?

SA: Yeah, we thought we were crazier than anybody else. And if we weren’t we’d do anything in our power to be more crazy. That was just our nature.

You said you were very young, 15, when you started going to shows. What did your parents say about that?

SA: Well, half the time my parents didn’t know when we were going to L.A. Half the time I was just telling them we were going to the skate park. I had my own car when I was 16. I was first. And I had a friend – she was a girl – who would drive us around before I had my license.

LM: That’s how skatepunk started actually. When the shows started being at the skate parks.

SA: That did happen. Yeah, it did. At “Pomona Pipe and Pool” they had a Devo day and then later on the Joneses and my band the Wild Ones opened up for them. Olson was playing in the Joneses at that time, so it was rad. Olson said, “Yeah, we’re gonna play. I’m gonna get you guys on the bill.” And it was rad. Even though we couldn’t play it was still fun.

What was your band called?

SA: Back in those days we were the Wild Ones. It was our very first band. We were all into Marlon Brando. We tried to play rockabilly, punk rock or whatever.

Thrasher Magazine came out in 1981. What do you think about the role of Thrasher in terms of music and stuff that? Because people tell me, “That’s where we learned about music; that’s where we learned about punk rock.” And you tell me all about the stuff that was going on before that…

The thing is, Mofo participated in a lot of stuff with us. He was there at the Clash with us and he was the guy who wrote for Thrasher. So he’d already been doing his version of punk rock since ’76 or ‘77. When I met Mo the first time, it was really early ’78. Probably at [the Hester Pro Bowl event at] Newark because he hung out with Kevin Thatcher and Rick Blackheart – and those guys came to skate with us at Upland all the time. So, that’s how we made that connection – San Jose and the San Francisco connection. Most of the guys who were from San Jose started Thrasher Magazine – Kevin Thatcher was the first publisher and editor and Mofo was the first big writer. That was their deal, too and it was do-it-yourself. Fausto founded the magazine and they just started doing what they had to do.

It appears that Thrasher is one of the first magazines that really seems to emphasize this connection to punk…

SA: I’m telling you man, Thrasher in those days, they actively participated in punk rock. Kevin Thatcher included – he would go to shows with us all the time, they all did.

LM: The Thrasher guys were skaters.

SA: Yeah, skated with us. They were the skaters. That’s what they did and they presented what they did and that’s why Thrasher in those days was a little bit different than it is now. All the dudes who wrote for the magazine, they all skated and went to shows. Mo has seen as many bands as I have seen in the city. Once we started riding for Indy I used to go up there a lot. We’d go to Fausto’s house and I would stay there for a week or stay in San Jose with Mofo, since there were all kinds of bands up there, too, that you wouldn’t see in L.A.

But I’ve seen pretty much every single band for the most part. Except for the Sex Pistols, ehm, what other band haven’t I really seen? I’ve pretty much seen them all really. Except for Generation X. That’s the one band I haven’t really seen. But everybody else… Saw Stiff Little Fingers, UK Subs, X. I thought Billy Zoom was rad as hell. The Germs…

LM: Do you remember the first band you saw? Punk band?

SA: The first punk band we ever really saw was 999 and the Dickies after some San Diego thing. That was the first show I remember going to. We weren’t really punk rock yet. We were on the verge.

SA: The first punk band we ever really saw was 999 and the Dickies after some San Diego thing. That was the first show I remember going to. We weren’t really punk rock yet. We were on the verge.

LM: Back then, you didn’t have to look punk rock to be punk rock.

SA: Yeah, I guess you’re right. But in my mind you had to really be punk.

LM: You went to shows earlier than me for sure but the first show I went to, there was a pretty broad spectrum of people.

What show was that?

LM: It was a band called Suburban Lawns. I don’t know how I ended up going there. None of the bands that we really knew or saw were around. It was a lot different when there was no internet. So you’d see an album cover – Blondie or Devo or whatever – and think: maybe this is a good one. But we never saw that they played anywhere. There was this place close to my house and we started going to shows of bands just because like Steve said all we wanted to do was jump around and fly on stage.

We were skating and we just wanted to get more aggressive. We were just stupid, basically. I went to a show and there was a guy doing back flips off the speakers. There was a circle pit and we’d jump from stage and there was a double stack of speakers above that and there’s this black dude doing back flips off of it. We’re just, “Dude!” We ended up talking to him and he was, “Oh, I skateboard everyday.” So, he came to our ramp the next day and he would ride up the wall, take a step from the wall and back flip off. That would be his trick. That’s all he did. He was the “back flip dude.” We’re, “This guy is gnarly!”

Then I remember going to a contest where they were playing Blondie, and I remember Steve’s Devo shirt.

SA: That was Lakewood then.

LM: Yeah, Lakewood. My dad is English and I went to England a few times thinking, ‘Ok, I’ve got to see this music. It’s punk. Were in England. Punk!’ Everything is going on. But punk was completely dead at that time in England. They were all into Motörhead and they were all gnarly…

That was when?

LM: That was ’79. I was thinking, ‘Ok, I’m gonna see all this stuff.’ I went to King’s Road and there was no punk music at all.

SA: When I went there in ’81 I thought I’d see the same thing but by then rockabilly was really big. The Stray Cats were coming in.

LM: So, I didn’t see bands until late. All the bands that we wanted to see weren’t really playing. It was very rare. The Clash came later. I saw them. Stiff Little Fingers… very rare. So were going to all this nonsense L.A. stuff.

SA: It was every weekend, there was something going on. Whether it was Alley Cats, The Plugz or…

LM: Out of all those bands I thought the Adolescents were actually interesting.

SA: Yeah, but they were a little later. We’d go to shows in L.A. and we used to see Mike Ness [from Social Distortion] we used to see Rikk Agnew. We didn’t really know who they were at that time. We didn’t know that until a little later after we started skating and they’d go, “Hey we saw you skating,” and blablabla and “I’m in this band called the Adolescents.” Mike Ness’s bass player was this guy Brent [Liles], we were good buddies and we used to skate at Pipeline; we used to skate at Skatopia. That’s how we met; it was through skateboarding. It was a small world and a group of people who really got into the first wave of all these really early early L.A. bands.

So at some point I said, “We’re gonna try do this ourselves.” But by the time you learn an instrument and get as good as you’re supposed to be the scene has changed. X was still around in ’81 but the Alley Cats weren’t. The Weirdos really weren’t. The Dickies still were. You’d still see Siouxsie and the Banshees at that point. Stiff Little Fingers had a big draw in L.A. The Clash had a big draw in L.A. The Vibrators had a pretty big draw, so…

So, what people today actually call or refer to as skatepunk that was something that came later?

LM: I think skatepunk is later when all the skaters started making bands. They did the same as the punk guys: ‘This is easy. I can play this chord. Why don’t we do this, too?’

A lot of skateboarders actually made up bands. That’s what skatepunk is, isn’t it?

SA: For me, when I think of skatepunk the first band that comes to mind would be JFA [Jodie Foster’s Army]. But I know those guys pretty damn good; I’ve known them for years. They don’t even really pitch with skatepunk cause that’s a term that doesn’t really span the horizon of what they are. At the same point they were definitely the forerunners of it. And they were regional, too. There was the Big Boys from Texas, JFA was from Phoenix.

Would you call Agent Orange a skatepunk band? It’s a term that’s a pigeonhole to me.

LM: Agent Orange were in a lot of skateboard videos. So, that’s why people would consider them skatepunk.

What skate videos would be…

LM: They were in a Vision video. I think the whole soundtrack was Agent Orange.

What other videos should I look at? What about Santa Cruz’ Streets on Fire?

SA: I was in those.

I mean, they’re full of SST bands, right?

SA: They licensed them out to Santa Cruz to get more exposure for SST, originally. But it was cool that we could actually use some of these bands. I was stoked on my couple of songs on there. To this day people ask me about those songs. It’s funny.

Which songs are you skating to in that?

SA: Well, there’s a song called Instro. That’s one I wrote. The one that goes, “Dadadada.” that’s my band and then I think we did Kings of Trash on the other one.

Could you choose the music for the videos?

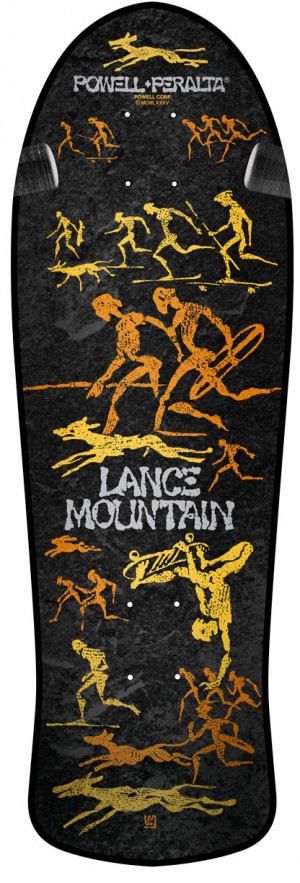

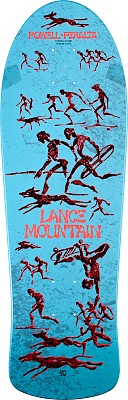

LM: No, when I rode for a company called Powell Peralta, Stacy Peralta made the first skate video. There were movies before but that was actually the first video made. We didn’t pick our music back then. I think they used Youth Brigade or something. But that was around ’84.

Well, when you mentioned the Suburban Lawns, just the name of it… It seems that in California the punk scene – especially the second wave, the Adolescents and bands like that – along with the skateboarding scene. That all came out of these suburban places. Do you think that plays a special role in how things developed?

Well, when you mentioned the Suburban Lawns, just the name of it… It seems that in California the punk scene – especially the second wave, the Adolescents and bands like that – along with the skateboarding scene. That all came out of these suburban places. Do you think that plays a special role in how things developed?

LM: Well I think anything out of L.A. is suburban. There is no downtown L.A. Every city is suburban, no?

SA: Suburbia is a thing that didn’t have to do anything with anybody at that time. It was more a label thing. It wasn’t ever a conscious thing. Some bands like The Descendents made fun of it. Suburbia is a theme in some of their songs.

So, you grew up in the suburbs, too?

LM: I grew up in East L.A, which is very… cholos. It was Mexican gangs. I lived right on the border of this very rich area but I was light years away from these skateboarders. I could skateboard to downtown in about 40 minutes but I thought I lived five states away from Hollywood when I was a kid.

SA: Where we lived the beach was how far away: 35 miles at least, 40 miles. We were definitely inlanders, and I always wanted to go to the beach but my mom and dad hardly ever took us. We’d go to the beach in the summertime maybe once a month. But I craved going to the beach. And I wanted to be a surfer. So, the closest thing to surfing was skateboarding – at least for me.

LM: I can say the same for me. I craved to be a skateboarder but I had to go to Montebello Skate Park. Montebello was the sad dwarf cousin of every skate park. It was outdated when it opened, while these guys were riding15 foot bowls.

SA: Yeah, our skate park [Upland?] was the first vertical skate park. It was gnarly, insane. Looking back now, I’m just stoked we got to skate that stuff. That’s where I learned. It’s pretty much the gnarliest skate park ever built, really, in the old days. At least old day skate parks.

When was that built?

SA In 1977. It lasted from ’77 to ’88.

Why did they close it?

SA: For insurance purposes. Couldn’t keep it afloat cause the economy was bad, too, at that time.

LM: Skateboarding was gone. Nobody skateboarded. A lot of the skate parks were pretty unsupervised. It’s a bunch of 13 to 18 year old kids basically at a summer camp on their own. It was a pretty high level of chaos and I think that the shows were just another place for that to happen even more extreme. Those early shows were pretty unsupervised. Anything could happen. There came a time in L.A. when they would not have punk shows any more, ever. Around The Decline of Western Civilization showings it was riots. Constantly.

SA: There was a riot at Santa Monica Civic, too, where ____ – I got to say this to get the whole thing – I was sitting right there when it happened, dude. He threw a beer bottle at a police car, right through the windshield. And then he got another beer bottle and threw it through the big old window of the front of the Santa Monica Civic. I was in the middle of pretty much every major riot that happened in L.A.

LM: It got to the point where the cop cars would just get lined up.

SA: First it was the weird art freaks, and then the skaters were mingling and then after the skaters got out, it was friends of skaters and then other weird whatever guys – and it was all those dudes that started the gnarliness. All the fights, the riots. It was unsupervised shows, there was hardly any security. It just e xploded, until the cops and the people just couldn’t take it anymore.

xploded, until the cops and the people just couldn’t take it anymore.

So how did skate parks fit into this? If you think about it, in terms of punk, you would think that skateboarders would say, “I don’t care about a skate park.” Because it seems as if it concentrates skaters where people can control them.

It was totally different than now. All the skate parks before were privately owned. A doctor and his son wanted to skate so they built a park. In the beginning they were trying to make them into realistic things but that didn’t work so they just became these empty wastelands and kids basically running themselves. They weren’t a controlled space.

Think about the alley in the back of the school where all the guys would go smoke and sniff glue. Oh, here’s the alley behind the school to smoke glue? That’s the skate park thing. Here’s our little place. We get in here, we control ourselves, no one comes in here. All sorts of chaos can happen. Everyone had bands upstairs. It was a club house. Totally different! Just a different time. I mean, there was two kids out of every city skateboarding that’d meet up so at the skate park there’s 15. Skate parks got really dead at the end of the 1970s. By 1980, they were dead.